By Camila Esguerra Muelle

“The notion of ‘global chains of care’ (Hochschild, 2000) is critical to understanding the connection between the economy of care and migration. However, we find that the way this concept has been theorized to be insufficient to understand the intersection and overlap between migration and care. This is the reason why I expand the concept proposing the term “Tramas transnacionales del cuidado” (Eguerra Muelle, 2019).

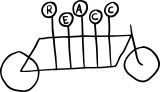

“The analytical category ‘global care chains’ refers to the complex network of local and global flows of care work that are primarily aimed at meeting the demand for care in urban areas and countries in the global north. That is, women from rural areas migrate to cities to join the precarious market of care work and, at the same time, those women or other women from southern countries migrate to northern countries to do the same.” “It is important to clarify that these flows also occur between countries of the south and to a lesser extent between countries of the north, as well as between rural and urban areas of the same country.”

“The first consequence of the displacement of these care workers would be what are called ‘care drains’ (Bettio, Simonazzi & Villa, 2006). These care drains, in turn, create care deficits in rural areas or in the countries of origin of these (usually female) workers — countries that are sustained by the badly or unpaid work of other women, children, and elderly women (and feminized people).”

“Thus, the care deficit in industrialized countries, or countries of the global north, is filled by the precarious work of women from countries of the global south — countries that, as they lose this precarious care work, start to experience their own care deficits. It is important to clarify that these flows also occur between countries in the south and, to a lesser extent, between countries in the north, as well as between rural and urban areas in the same country.”

“Under these local and global care chains, we encounter an international and gendered division of labor, one that results in the drain of the jobs and knowledge of care. However, what we propose is that this international division of care is not only gendered but also racialized, that is, it is a colonial division of labor governed by colonial racial difference and gender coloniality (Lugones, 2007; Berker & Feiner, 2009).”

“In the case of Colombia, we find that the way global care chains have been conceptualized does not fully account for how and why women (and feminized subjects) become trapped in care chains, since in Colombia, according to the collective account that we have managed to construct through our research, the care drain can be traced back not only to the demand of cities and countries in the global north such as Spain or the United States, but to a long colonial history marked by war; an expression of both internal and external colonialism. The concept ‘tramas transnacionales del cuidado’ (Esguerra Muelle, 2019) allows us to study the global care chains in a the context of both, internal and external colonialism.”

“The armed conflict in Colombia, which we can say began with the 16th century European invasions, is not just an internal conflict involving official and non-official armies, as well as business, government, and local civilian officers (at times there are grey areas between who might be considered a civilian and an armed officer). Rather, it is a conflict for which international actors (corporations, governments with interventionist policies, extractivists, gentrifiers, and supranational organizations) are responsible, and consequently the war in Colombia can be understood as a demonstration of internal and external neocolonization.”

“The war in Colombia has forced millions of women into exile, women who are then victims of subsequent displacements (or of a never-ending displacement) and of seemingly voluntary migrations. The increasing poverty and terror that shape the social and armed conflict in Colombia are the conditions that force these women to leave their homes. Through this exodus they remain trapped in local and global care chains.” (Esguerra Muelle, 2018)

English translation – Carinna Nikkel

Bibliography:

Esguerra Muelle, Camila, Sepúlveda Ivette & Fleischer, Friederike (2018) Se nos va el cuidado, se nos va la vida: Migración, destierro, desplazamiento y cuidado en Colombia Documentos de Política No. 3 ISSN 2538 – 9491. Diposnible en: https://cider.uniandes.edu.co/es/publicaciones/node%3Atitle%5D-81

Esguerra Muelle, Camila. (2019). “Etnografía, acción feminista y cuidado: una reflexión personal mínima”. Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología 35: 91-111. https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda35.2019.05

Esguerra Muelle, Camila (2019a). Complejo industrial fronterizo, sexualidad y género. Tabula Rasa,33, 107-136. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25058/20112742.n33.05